Boyce's Legacy

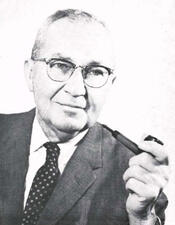

The College of Natural and Agricultural Sciences owes much of the credit for its current strengths and reputation to a reluctant administrator, Alfred Mullikin Boyce.

Dr. Boyce led the college as its first dean from 1960 to 1968, a period of dramatic growth and changes, but he had come to the position over his own objections. As he wrote in his 1986 autobiography, he had declined three times to take the job as director of the Citrus Experiment Station. In spite of Dr. Boyce's repeated refusals, UC deans kept asking until in 1952 he finally said yes.

Dr. Boyce quickly went to work to expand research, teaching, and outreach efforts in response to a growing Southern Californian commercial and agricultural economy. He introduced new research programs in biostatistics, nematology, air pollution, desert agriculture, and vegetable crops — programs that distinguish the college today and are among its most widely recognized. Also during the same period, student enrollment tripled, seven laboratory and research buildings were constructed, and 1,150 acres of land were acquired for establishment of research farms.

For all his achievements as a manager, Boyce regretted that his role as administrator had required him to forfeit teaching and research. "Even though I found great challenges in administration," he wrote, "I envied those entomologists and other colleagues who were responsible only for research and teaching."

Boyce's prior work as an entomologist had been distinguished. After joining the Citrus Research Station in 1927 while earning his doctorate from Berkeley, he started traveling frequently to India, Africa, and Asia to find natural enemies of citrus pests. In the process, he discovered dozens of new species of insects and mites, with four named boycei as a result. He also played a crucial role in efforts to suppress the walnut husk fly and parasitic wasps that spread disease in olive crops.

Dr. Boyce had chosen entomology because of personal experiences. Having worked on the family farm in Maryland until his high school graduation in 1918, he understood the value of combating agricultural pests. And as one of 70 merchant seamen bothered by lice and bedbugs when wrongfully imprisoned in Naples, Italy, for several months, he recognized that advances in the field also would benefit city residents.

The seafaring aspect of his character was very strong. Although many faculty have written about Dr. Boyce as a highly self-disciplined and exacting administrator, he was just as strongly a free spirit. Before entering Cornell, he had led a nomadic existence, living for a brief time as a hobo, hopping trains and making his home on Florida beaches as he searched for work. Remnants of his youthful abandon remained after he came to Riverside.

Not only did he continue to travel to exotic places — although taking his wife, Janet, and three children with him — but, he recalled, some considered him to have rough behavior. In fact, he was denied tenure three times because a fellow entomologist objected to his speeding while driving university vehicles, his use of profanity, and his cigar smoking and occasional drinking.

In spite of these characteristics, he became one of UCR's most recognized leaders, receiving an honorary doctor of law and recognized by the naming of a building and an endowed professorship.

He and Janet moved to New York after retirement so that Dr. Boyce could consult with the Rockefeller Foundation, which was developing a grants program in environmental quality. He worked with the group until 1974, finally returning to Riverside. Until his death at age 96 in July 1997, he lived a quiet life with only an occasional trip around the world.